Why I Won’t Ride Elephants

Elephant Nature Park: Now & Then

I volunteered at the Elephant Nature Park for one week in the summer of 2013. At the time, around 30 rehabilitated working elephants received refuge there from logging, trekking, forced breeding, street begging, and circuses. The aging female herds cherished the two babies at the park, the weeks-old female, Dak Mai, and the rambunctious boy, Navaan.

Now, more than 70 elephants—and 500 dogs, 200 cats, and few herds of cows and water buffalo—live at ENP. That means that more elephants escaped harmful conditions, including one elephant from a neighboring trekking camp who actually broke down the boundary fence so many times that the trekking owner finally sold her to the park. That also means that new, energetic elephant babies and teenagers are born or raised at the park, never enduring the tortuous “crushing” experience that trains them to obey humans.

ENP’s growth is made possible by the people who visit and volunteer at the park. Now, 20 busses bring visitors from Chiang Mai to ENP every day. They drink ENP coffee, grown sustainably by local women. They buy wooden elephant statues, crafted by Burmese mahouts. They donate money and adopt dogs.

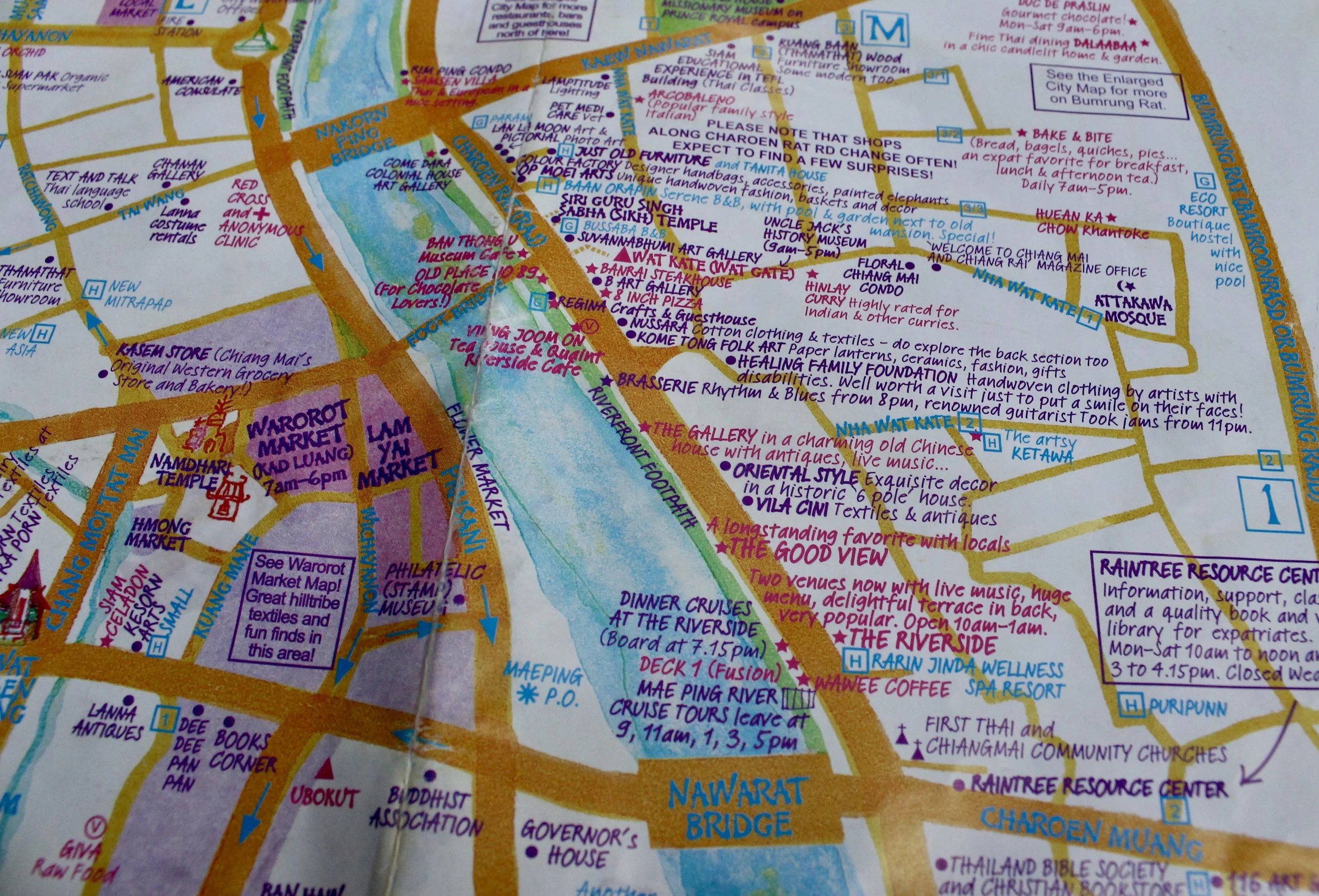

Four years ago, the park’s voluntourism model and no-riding rules were relatively new in Thailand. You won’t find ENP brochures in hostels or see advertisements on city sidewalks, but replicas of the park’s sustainable and ethical model proliferate.

I’m happy that the park is expanding and its philosophy is spreading, but growth can be problematic. There are more than double the number of elephants at the park, but no more acreage for them to roam. More humans interact with the elephants during nature walks, river baths or feeding time—making their environment less natural and empowering.

The goal is to free the elephant, but this is not quite what freedom looks like. It’s a tough spot to be in—they have grown enough to rescue more elephants but not enough to buy more land—and it’s sad to see. They have plans for future land expansion, but it will take time.

Responsible Elephant Husbandry

It’s more common these days for tourists in Thailand to request responsible elephant husbandry, but many people are still unclear about what that means. It certainly can be overwhelming to sift through dozens of elephant experience possibilities when they all claim to be harm-free.

Despite its complex expansion issues, I believe that ENP still does a fantastic job teaching about elephant anatomy and behavior. This helps explain its ethical choices, like no riding elephants. I believe in ENP’s philosophy, and I will never ride an elephant.

In basic terms, here’s why:

Elephants are so heavy that they need to readjust their body and alignment every few steps. They spend 20 of 24 hours each day eating actual tons of food. When they wear a saddle on their back and are prodded along by their owners to keep moving, they don’t get what they need.

They don’t eat enough food or drink enough water. The saddle deteriorates their spine. And to stay “calm” enough for you to be on their backs requires a history and continuation of physical punishment.

Almost more heartbreaking to me than the physical treatment that elephants endure in this type of work is the disruption of the elephant social structure. Female families stick together, and they have deep and complex social connections. They mourn their dead. They protect their young, and they truly don’t forget their friends. The elephant trade—which trekking is a part of—traumatizes and separates families.

Both now and then, the most impactful thing for me at ENP is witnessing the undeniable spirit of elephants. They love and forgive and practice resilience. Many elephants came to this park alone, their family stolen from them. But they’ve chosen new family groups, and their fierce friendships are pretty inspiring to see.

By Mel Grau